Engagement, especially when qualified with words like community, public, or civic, shows up in a lot of contexts. I recently wrote a post about librarians as engagement leaders, and in this post I want to follow up a bit further regarding my current thinking about the purpose of engagement. In a 2012 paper about community-based research, Randy Stoecker describes two forms of social change that I think apply more broadly than just the academic setting. First, there is the need for action to address specific issues — a group’s need or opportunity. But when done using a fully-participatory process, a second form of social change is achieved that transforms the social relations of knowledge production. A liberative form of community engagement is done in ways that both address a specific issue and also increase the capacity of those with whom we are engaging to become knowledge producers so that their own knowledge can inform group action and build group power.

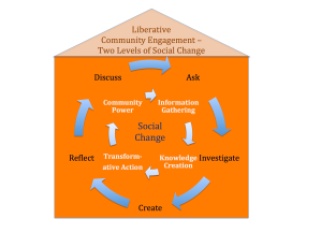

The diagram on the left is my visualization of these two forms of social change. At the center, the central goal of liberative community engagement is to bring about social change. The outer circle represents the community inquiry and inquiry-based learning as described by Chip Bruce — “inquiry conducted of, for, and by communities as living social organisms.” The outer circle could as easily have been comprised of the community-based research steps of diagnosis, prescription, implementation, and evaluation as described by Stoecker. Indeed, there are a number of useful models for participatory action leading towards addressing a specific issue. The two mentioned are also examples of methods whose underlying objective is the inner circle of social change, that of building community power by fostering community’s increasing role in information gathering, knowledge creation, transformative action, and ultimately community power.

The diagram on the left is my visualization of these two forms of social change. At the center, the central goal of liberative community engagement is to bring about social change. The outer circle represents the community inquiry and inquiry-based learning as described by Chip Bruce — “inquiry conducted of, for, and by communities as living social organisms.” The outer circle could as easily have been comprised of the community-based research steps of diagnosis, prescription, implementation, and evaluation as described by Stoecker. Indeed, there are a number of useful models for participatory action leading towards addressing a specific issue. The two mentioned are also examples of methods whose underlying objective is the inner circle of social change, that of building community power by fostering community’s increasing role in information gathering, knowledge creation, transformative action, and ultimately community power.

It is right to recognize that sometimes any aspect of these cycles may require a significantly specialized expertise. Engagement may thus include our providing services to the community in support of their social change projects to meet these specialized needs. But an ally approach to engagement requires that we are very careful to first critically consider such a step in light of the differences in power and privilege that exist. Anne Bishop notes

Allies are people who recognize the unearned privilege they receive from society’s patterns of injustice and take responsibility for changing these patterns.

Who is driving the decision to provide a service to the process instead of working to transform the nature of knowledge production by working with people to advance their own ability to accomplish the service? “Expediency” and “efficiency” can as easily be buzzwords for maintaining the status quo of power differences.

Engagement as I am increasingly thinking of it is a process of deep, critical, difficult dialog. A presentation at the Engagement Scholarship Consortium recently by Emerge Solutions, Inc. introduced me to the concept of the groan zone. As with normal brainstorming, ideas are brought to the table to expand our consideration of how to proceed. But unlike brainstorming that is working to achieve a certain goal, the divergent phase doesn’t pretend to know what the end point is or what it means. The divergent phase is instead about simply about idea generation. Along the way, the conversations may and often do become uncomfortable. The process may be terminated too soon to really work through these discomforts. But by continuing the process through the groan zone and to the divergent phase, new, often truly important, ideas come because of the difficult conversations.

As with normal brainstorming, ideas are brought to the table to expand our consideration of how to proceed. But unlike brainstorming that is working to achieve a certain goal, the divergent phase doesn’t pretend to know what the end point is or what it means. The divergent phase is instead about simply about idea generation. Along the way, the conversations may and often do become uncomfortable. The process may be terminated too soon to really work through these discomforts. But by continuing the process through the groan zone and to the divergent phase, new, often truly important, ideas come because of the difficult conversations.

Maria deBruijn of Emerge Solutions suggested in their presentation at the Engagement Scholarship Consortium that too often consultants work to minimize the discomfort and to “facilitate” the process by putting the groan zone into a black box because it is such difficult work. But in keeping this work hidden, consultants ultimately limit or eliminate the opportunity for deeper community building. Digital technologies further hide the difficult work in many cases, which is why Emerge Solutions carefully consider if, when, and which digital technologies to incorporate into the dialog processes on which they are consulting.

I think this is a great example of liberative community engagement! From their website, deBruijn writes about her experiences leading to the formation of Emerge Solutions:

Over the years, she noticed that clarity (a strong vision), cohesion (relationships) and resilient communities (the ability to adapt together) emerge when people invoke leadership and actively engage others to plan and make decisions.

She also noticed that leadership and engagement can come from any place in a community and organization, and that it stands up even in the face of complexity, polarities, and the chaotic conditions that tend to plague progress and sustainable courses of development.

A number of interesting articles are surfacing with regard to the role of public libraries in community in response to the radical hospitality the Ferguson Public Library demonstrated following the shooting of Michael Brown and again after the grand jury decided not to indict Darren Wilson, the officer who shot Brown. A 2012 blog post by R. David Lankes was revisited in the midst of the conversation. In that post, Lankes clarifies:

You see a good library sees the collection as a service and therefore monitors and plans for its use. A great library sees the collection as only a tool to push a community forward, and more than that, they see the library itself as a platform for the community to produce as well as consume. The library member co-owns the collection and all the other services offered by the librarians. The library services are part of a larger knowledge “eco-system” where members are consuming information yes (a user), but also producing, working, dreaming, and playing. That is the focus of a great library. They understand that the materials a library houses and acquires is not the true collection of a library – the community is.

Engagement isn’t simply providing services. When a library develops a strong collection of books, this often is a valuable service to the community, especially when done strategically. But such a community service is not engagement. When a school makes available classes to the broader community at no cost, this is potentially a valuable outreach service to the community. But outreach isn’t engagement, either. Doug Borwick’s does clarify that such outreach could be thought of as audience engagement, where the goal is increasing the “number of butts-in-seats/eyes-on-walls”. But this remains a service to rather engagement with. Hildy Gottlieb compares this to the “‘Tell and Hope’ method of communications: I tell you my story, and I hope you will do what I want you to do.” Generalizing from the Tufts distinction of outreach vs. engagement for the university, outreach expands the reach of programs, services, activities, or expertise, but it is one-way, with the organization providing contact or a service to the non-traditional audience for the contact or service.

Real engagement is difficult. Real engagement expects conflict and embraces it as important in coming to understand the other side of the story. Steve Sullivan, who runs a network of counseling and crisis centers called Provident in the St. Louis area, was recently interviewed on the National Public Radio program morning edition following the grand jury’s decision in the Michael Brown case. In the interview, Sullivan stresses the importance of working to understand each other. But in being open to conversation, we need to embrace “being uncomfortable in your conversation. You know, going somewhere to sit down and talk to people that you would have never thought about before.”

Returning to the diagram, then, when we ask questions, we need to ask in ways that also help us to address critical questions about privilege and ways to change the system, not just the superficial questions regarding a symptom of the problem. This is radical in the original sense of forming the root. When we investigate, we need to be expansive in those investigations to seek the emergent understandings, not just the easily accessible information. Later, our discussions need to include people we would never have thought about before so that we can understand the many different sides of view of the investigation and action/creation. This is a very different kind of knowledge creation and transformative action that supports creation of knowledge power. And it leads to new cycles of information gathering, knowledge creation, and transformative action.

Engagement has often been described as mutually beneficial as opposed to services that are designed to flow from the giver to the receiver. But mutually beneficial is a complicated concept, especially when we recognize engagement is often performed between groups with different intersections of privilege and power. Martin Luther King, Jr. once said “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Perhaps a more helpful way to understand mutually beneficial, then, is to recognize that social change that transforms the social relations of knowledge production by changing society’s patterns of injustice. And when it does, we all benefit because of the more just society. This isn’t a product, it’s a process. This form of social change isn’t delivery of a thing, it’s the liberative dialog between people. And it changes everyone and everything.

0 thoughts on “Engagement and Two Forms of Social Change”