In 2010 I spent over half the year in East St. Louis helping to develop a set of grant proposals requesting a bit over $32 million in federal stimulus funds. Little did I know this would be my capstone project as changing funding priorities increasingly pulled me away from a community I had come to deeply love after more than a decade of engagement.

The grants, if funded, would have built much needed broadband infrastructure, public computing centers, and digital literacy programming. In the paper “Innovation Diffusion and Broadband Deployment in East St. Louis, Illinois, USA“, Lisa Bievenue and I reflected on lessons learned from the experience using Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation theory. The expansive theory has many components, but of particular note for us was the social communication process that fosters diffusion of an innovation throughout a defined population.

For Rogers, innovation is defined very broadly as an artifact, concept, or practice that is new to the population. His book identifies a wide range of innovations, from contour plowing to birth control to a digital technology. This proved valuable for us in that it allowed us to see cases of innovation diffusion in East St. Louis even if limits in resources limited digital innovation specifically.

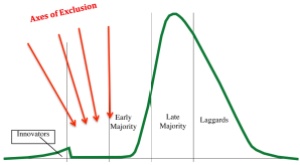

Using a bell curve, Rogers divided a population adopting an innovation into five categories: the innovators, the early adopters, the early majority, the late majority, and the laggards. I’m not clear whether the terms used were meant to be value-laden when Rogers first proposed his theory in the 1960’s, but they certainly are today. We celebrate the innovator and innovations as generally positive and increasingly valuable if we are to solve the problems of today and thwart the potential problems of tomorrow. Laggards, then, are seen as hinderances to achieving that promise.

Using a bell curve, Rogers divided a population adopting an innovation into five categories: the innovators, the early adopters, the early majority, the late majority, and the laggards. I’m not clear whether the terms used were meant to be value-laden when Rogers first proposed his theory in the 1960’s, but they certainly are today. We celebrate the innovator and innovations as generally positive and increasingly valuable if we are to solve the problems of today and thwart the potential problems of tomorrow. Laggards, then, are seen as hinderances to achieving that promise.

In this article I’d like to challenge that unquestioned valuing of innovation, though, and so I will instead use language pulled from the descriptions of these categories to instead label them: the tinkerer, the opinion leader, the cautious, the skeptic, and the traditionalist. Rogers also defines the change agent, who’s role is to come in from the outside to help affect change by fostering diffusion.

When we work to address the “digital divide”, the assumption is that for multiple reasons certain communities lack access to the physical and educational resources to participate in our digital age. The goal of such programs is to distribute the technologies that the “haves” enjoy to the “have-nots”, and to provide the needed digital literacy so that they can get onboard before they are further left behind.

When we work to address the “digital divide”, the assumption is that for multiple reasons certain communities lack access to the physical and educational resources to participate in our digital age. The goal of such programs is to distribute the technologies that the “haves” enjoy to the “have-nots”, and to provide the needed digital literacy so that they can get onboard before they are further left behind.  We deplore the lack of human resources that leaves communities without the important tinkerers and opinion leaders that would otherwise have been able to see the competitive advantage they could have gained through early adoption of innovations. From this lens, the adoption curve is highly skewed to the right side of the curve, and innovations encounter a wall of resistance. As such, we redouble our efforts to urgently reach the non-adopters.

We deplore the lack of human resources that leaves communities without the important tinkerers and opinion leaders that would otherwise have been able to see the competitive advantage they could have gained through early adoption of innovations. From this lens, the adoption curve is highly skewed to the right side of the curve, and innovations encounter a wall of resistance. As such, we redouble our efforts to urgently reach the non-adopters.

But using Rogers broader conceptualization of innovations, Lisa and I began to notice that with many non-digital technologies, and even with some digital technologies, East St. Louis had as many tinkerers as did Urbana-Champaign, the hometown of the University of Illinois’ flagship campus. And Urbana-Champaign had as many traditionalists as East St. Louis. But with digital technologies, those who would typically be the important opinion leaders fostering diffusion to the broader community were waylaid from those roles as they worked multiple jobs to make ends meet in addition to serving as civic leaders.  As such, they had limited discretionary time or income to play a critical role on behalf of their community. Combined with other axes of exclusion, then, the community did not have the full complement of players to help assure a classic diffusion of innovation model. With this lens, the work is to build capacity for the existing innovators and early adopters rather than to more generally distribute innovations from the outside into the community. But it is to also work as allies to the oppressed to identify and work to challenge the axes of exclusion, much of which is institutionalized within societies laws, policies, practices, and culture to privilege some over others.

As such, they had limited discretionary time or income to play a critical role on behalf of their community. Combined with other axes of exclusion, then, the community did not have the full complement of players to help assure a classic diffusion of innovation model. With this lens, the work is to build capacity for the existing innovators and early adopters rather than to more generally distribute innovations from the outside into the community. But it is to also work as allies to the oppressed to identify and work to challenge the axes of exclusion, much of which is institutionalized within societies laws, policies, practices, and culture to privilege some over others.

From this framework of diffusion, colleagues and I have been working to develop a demystifying technology approach to digital literacy, an approach that is as much and more about demystifying the social as the technical that comprises a digital artifact.

But there has been another aspect to the curve that has been nagging at the back of my mind for some years and which I’ve been grappling with at the edges. It is the embedded value we give to innovations and those who bring them to new communities. Such a valuation is to assume that struggling communities are missing something — an innovation — that will fix their problems. As such, progress is defined in terms of needed new technologies and practices. This fits well our economic model that depends on growth if the nation is to remain healthy and thriving. But does unquestioned valuing of innovations truly advance human flourishing? Are market forces the best method for separating the good innovations from the bad?

Perhaps in our insistence to reform the skeptic and the traditionalist so that they no longer stand in the way of progress and instead join the enlightened, we’ve lost an important counterbalancing voice. Let me be clear, I do not say this because I romanticize a past that has often been equally and even more exclusionary and oppressive, albeit in different ways. But to race away from the time-honored ways championed by traditionalists and to ignore the warnings of the skeptic, I believe, is to run headlong off an unknown cliff where solid ground has been eroded away by the waves of progress. Such an approach is to allow the exuberance of the tinkerer and the passion of the opinion leader to have domination over the ideas of others.

I instead am increasingly inclined to see the value in embracing another way, a way that works to integrate the ideas of the innovator, the insights of the opinion leader, the caution and skepticism of those in the middle, and the time-honored of the traditionalist. It is to embrace difference as a resource, where every perspective is sought and prized as important if we are to find emergent approaches to what are primarily social issues.

Change agents, rather than working to colonize a community through enforcement of outside values and goals, or working to promote the regime of the tinkerer, instead seek to foster community dialogue so that all voices can be heard. Change agents also work as allies to report back to those outside a community the ways in which systematized oppressions are serving to exclude the community, or certain voices within the community.

As for digital literacy programming, I am increasingly inclined to believe we need places where tinkerers, traditionalists, and all those in between come together to dialogue and learn from each other, as opposed to putting the technology expert at the head of the class to distribute knowledge to the unknowing student. We need to use dialogue to probe everyone’s expertise, so as to explore how and why we should appropriate an innovation, and how and why we should hold on to the time-honored ways. Further, it is to seek wisdom from the cautious and the skeptic to heighten our ability to critically question who might gain privilege and who might be oppressed through adoption of specific implementations of an innovation. And it is to see who and how use of an innovation might be humanizing and dehumanizing, and to develop and enforce policies that increase the former and work to eliminate the latter.

Both Fab Labs and Makerspaces have at their core a more radical approach to innovation that seeks to challenge the current industrial model of innovation, one that has most people awaiting the innovations that come from the “experts” that work for major companies. These innovations spaces work to reassert the garage tinkerer into the drivers seat of innovation, which is good. Tinkerers and early adopters within a community are much more aware of their community and its values and goals than a national or international corporation ever could.

But I am skeptical whether places like Fab Labs and Makerspaces can be sites where all voices in community come together in dialogue as described above. Their names alone prioritize the tinkerer over the traditionalist.

As such, I think there is need for another public place, and I think the library is an excellent choice. When properly designed, equipped, and staffed, the library can serve as a place where all members of a community are welcomed. A library that aggressively works to identify and challenge ways in which it is excluding some from the community, and that works to equip both the tinkerer and the traditionalist with the resources they need to accomplish that which they value being and doing, can be an essential site for community conversation and community building.

A tinkerer, a traditionalist, and a change agent walk into the library one day…

… to build a more resilient, inclusive, community together.

Thank you for your thoughts. Finding ways to honor and inform the traditionalists while not putting up roadblocks for the tinkers and change agents has been one of, my toughest challenges as a manager. We call our room of technology tools a Re-Maker space. Libraries have long been about ways to acquire knowledge and put it to use. The things we are doing with scanning, photo editing, transferring home VHS to digital formats are as important to our space as the 3D printers. Framing our mission to convey that heritage has made the transition much more palatable to many here.